Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Quick Links

A Short History of the 1792 Half Disme

Collectors’ Note: July 2017 marked the 225th anniversary of the minting and distribution of the first United States coins into circulation. During that month, secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson, ordered, received and distributed the 1792 half dismes. Jefferson's role with respect to these coins has only come to light in recent years thanks to the publication of the book, 1792: Birth of a Nation’s Coinage by Pete Smith, Joel J. Orosz and Leonard Augsburger. Prior to this, numismatic writers and collectors believed that George Washington was deeply involved with these first coins. Here is a brief review of the history of the 1792 half disme as numismatic researchers view it today.

Introduction

The Coinage Act of 1792, provided the initial authorization for the monetary system that we enjoy today. It called for the construction of a mint in the capital city of the United States, which was then Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and set the standards for ten coin denominations, from the half cent to the ten dollar gold piece or “eagle.” Among those ten denominations, the half cent was discontinued in 1857, and the last $2.50 gold pieces were issued in 1929.

Eight of the original denominations are still made today, although in vastly different formats. The copper cent is now made of zinc with a copper coating. The silver coins, except the dollar, are copper-nickel clad pieces. The latest dollar coin is made of 77% copper, 12% zinc, 7% manganese and 4% nickel. The gold denominations are represented by paper. Yet, it is remarkable that so many things have remained the same.

In an odd twist of assignments, President George Washington placed secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson, in charge of the mint instead of treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton. In that position Jefferson played the leading role in the production and distribution of the first United States coins.

Thomas Jefferson Orders the First 1792 Half Dismes

For many years it has been said that George Washington donated his personal silverware for the production of the 1792 half dismes. The Washington connection has been further romanticized by the claim that first lady, Martha Washington, was the model for the bust of Liberty that appears on the obverse of the piece. Those stories are myths, but the real history, which was documented by Thomas Jefferson in his Memorandum Book where he noted his daily activities, is almost as engaging.

Carpenters' Hall, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was the first location for First Bank of the United States until a permanent building opened in 1795. Thomas Jefferson came here to withdraw $100 from his account before he made the arrangements to have the 1792 half dismes made.

On July 10, 1792 Thomas Jefferson withdrew $100.00 in silver coins from his account at the first Bank of the United States. We don't know all of the types of silver coins that may have been part of that withdrawal. It would be safe to say that the majority, if not all of those coins, were Spanish Milled Dollars, probably both the Pillar and Portrait types.

Pillar Type Spanish Milled Dollar

The next day Jefferson made the rounds with those who were making the arrangements to establish the first mint, including David Rittenhouse who had been appointed the mint director. The mint property had not yet been purchased so it is likely that Jefferson met Rittenhouse at his home. The Rittenhouse residence was half a block from where the facility would be located at the corner of 7th and Arch Street. Jefferson consigned $75.00 of his silver to Rittenhouse who drew up a receipt for the bullion. Jefferson was exercising a right that would be available to all Americans. Individuals and businesses could deposit gold or silver bullion at the mint where it would be converted to coinage for little or no charge.

This 1792 half disme was made before the dies rusted and broke. Therefore it was among the pieces that Jefferson received before he began his journey to Monticello. It is possible that he could have handled this piece personally.

Jefferson took his silver to John Harper's saw maker's shop which was two blocks from Rittenhouse's home on the corner of Cherry and 6th Street. Previously Harper had been involved in the production of the New Jersey coppers at the Rahway Mint. Jefferson's coins were melted, formed into ingots, rolled into strips, cut into planchets and struck into 1,500, 1792 half dismes. On July 13th, Jefferson noted in his Memorandum Book, "Re'cd from the mint 1,500 half dismes of the new coinage." All of steps to produce the 1,500 half dismes had been completed in just two days, or were they?

It has been theorized that the silver for the 1792 half dismes was in process at the time that Jefferson delivered his silver to John Harper’s facility. Perhaps the silver had been brought up to the legal alloy standard, formed into ingots, rolled into strips and even cut into planchets before Jefferson arrived. This might explain how so much seemed to be accomplished in only two days’ time.

It would also explain how 75 silver dollars could appear to be converted exactly into $75 dollars’ worth of half dismes. Given wastage and the left over silver from the planchet cutting process, no mint operation could produce an exact result like that. More than 75 silver dollars would be required to complete the project because scrap silver would be left over after the work was completed. Unfortunately we will probably never know the answers to these questions.

The new coins featured a small bust of Lady Liberty on the obverse with the date "1792" below. The legend, "Lib. Par. of Science & Industry" ("Liberty Parent of Science and Industry") ran around the edge of the design. The reverse featured a small eagle in flight which was surrounded by the motto, "Uni. States of America." The denomination "Half Disme" was below the eagle with a star below those two words. The edge was marked with diagonal reeding.

One unusual feature of this design was that the face value of the piece was defined on the coin. Subsequent issues of silver and gold coins would have scant references to their face values if there was any mention of them at all. No mention of value was made on the early half dimes and dimes minted before 1809. The Draped Bust, Heraldic Eagle Quarter had "25 C" on the reverse, while the half dollars and silver dollars had their values marked around the edge. There were no marks of value on the gold coinage from 1795 until 1807 when designer John Reich placed "2 1/2 D." and "5 D." on the $2.50 and $5.00 gold coins.

This 1794 half dime bears no markings as to its face value.

Jefferson Distributes Coins

For all of the 18th and much of the 19th centuries, the Federal Government essentially shut down in the summer. Jefferson and his daughter, Mary "Polly" Jefferson, set out on their trip, by coach, to his Virginia home, Monticello, on the afternoon of July 13. Jefferson carried with him the 1,500 half dismes he had collected from John Harper that day.

They traveled about 18 miles to Chester, Pennsylvania where Jefferson recorded the first dispersal of the new coins into circulation. In a note he recorded that he paid 30 cents in tips to "servants." This was the first time that Jefferson had noted a payment in the new system that used "cents." Jefferson's previous entries had been made in Spanish Dollars or their fractional parts that were divided into eighths or the British system of pounds, shillings and pence.

Jefferson continued to distribute the new coins as tips to servants and sometimes as gifts to children throughout his trip to his home. He passed through or stopped at Christiana, Delaware, Elkton and Baltimore in Maryland, Georgetown and Elkrun Church in Virginia and other locations. During his trip he had distributed at least 39 half dismes. He had other expenses during his trip, and it is impossible to determine if he spent any half dismes when he paid those amounts. The expenditures might have been paid in Spanish dollars or other currencies.

After Jefferson arrived home on July 21, He continued to spend half dismes to cover part of his plantation expenses. He recorded $54.00 income and $63.15 in expenses during that summer. There is no record as to origins of the coins that he spent on his plantation expenses, but given that the amount ended in the number "5" it is probable that he spent more half dismes during this period.

Jefferson left Monticello to return to Philadelphia on September 27, 1792. On his return trip he passed though the same cities and towns he had visited in July. The amounts spent indicate that he may not have had any half dismes left to distribute. Many of the tips or "vales" were in amounts like .166 that indicated the use of the smaller Spanish silver coins.

One of Jefferson's stopovers was a visit with George Washington at Mount Vernon on October 1. It has been claimed for many years that Washington personally handed out some of the 1792 half dismes. Washington could not have obtained any of the coins in July because he had left Philadelphia before Jefferson had received his half dismes. If Washington handled any of the original mintage of 1,500 pieces, he would have had to have obtained them from Jefferson during this visit. Jefferson's records do not indicate that he gave any half dismes to Washington or exchanged any coins with him. The assumption is that Jefferson did not have any 1792 half dismes in his possession when he arrived in Philadelphia on October 6.

A Possible Second Mintage of 1792 Half Dismes

There have been indications that the Philadelphia Mint personnel produced a second run of 1792 half dismes in the fall of 1792. In 1860 mint director, James Ross Snowden, wrote that additional half dismes and some pattern coins were struck at that time after the mint received three coin presses from abroad. Snowden obtained this information from the account book of the mint's first chief coiner, Henry Voigt. Henry Voigt's first account book has been lost, and all of this information comes to us second hand. It was said to 200 to 300 half dismes were minted at that time which would have brought the total mintage to 1,700 to 1,800 pieces.

The small surviving number of 1792 half dismes provide evidence that this second round of coinage took place. Some pieces show die breaks and die rust, which proves that those pieces were made some time after the initial July coinage. Die rust is commonly seen on 18th and 19th century Philadelphia Mint coins because the humid climate in the city often promoted die deterioration, especially in the summer. Since the July coinage was produced in only two days, there is no way that the dies could have rusted during that short period of time. This provides some proof that additional coins were struck sometime after July.

This second coinage brings up some interesting questions. Who provided the silver for this second coinage of half dismes? Who was involved in their distribution? Could it have been that George Washington provided some of the silver? Did Washington distribute any of the coins from this second run? There is no evidence that he did, but given the possibility that he might have been personally involved with these coins, the old legends that Washington provided silver and distributed some of the coins to officials and diplomats might be given some new life.

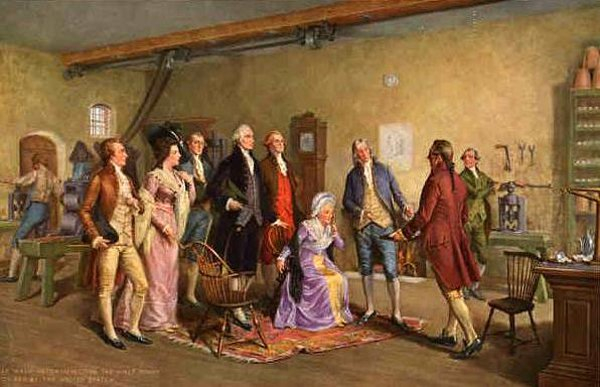

"Washington Inspecting the First Coins" by John Dunsmore. The drawing hung on the wall in the background would indicate that the coins under inspection were 1792 half dismes. From Wikipedia Commons, in the public Domain.

Who Made the Dies for the 1792 Half Dismes?

Although no artist's name or initials appear on the half disme design, a comparison of the bust of Ms. Liberty on the coin strongly suggests that Robert Birch, who signed his name to the Birch Cent pattern also made the dies for the smaller silver coin. Not much is known about Robert Birch. In fact some researchers are not even sure that his first name was Robert. Those who would like to review the historical speculations concerning this gentleman may consult the beginning of chapter 6, "The Art and Artists of 1792" in the recently published book, 1792: Birth of a Nation's Coinage, by Pete Smith, Joel J. Orosz and Leonard Augsburger.

The 1792 Half Disme as a Collectors' Item

The 1792 half disme has been a collector's treasure for as long as there have been American numismatic hobbyists. The first mention of it from the books in my library, was in Sylvester Crosby's The Early Coins of America which was first published in 1874. Harold P. Newlin covered it in 1883 in his "Classification of the Early Half-Dimes of the United States" calling it "the rarest of the series, excepting the 1802 Half-dime." Modern researchers would not agree with that rarity rating.

In 1958 Walter Breen in his "United States Half Dimes - A Supplement" ("A supplement" to Daniel Valentine's pioneering half dime work) described it as, "Probably the most desirable American small silver coin." Today, given the obsession that so many collectors have with rarity, the 1802 half dime probably holds that honor. But for those of us who appreciate history more than rarity, I find the 1792 half disme far more interesting. All one can say about the 1802 half dime is that an estimated 3,060 were minted and only about 35 of them survive today. Beyond that the 1802 five cent piece has no unique history or points of interest.

The estimated surviving population of the 1792 half dismes ranges from two to three hundred pieces. Although there are about 20 pieces known in Mint State, the vast majority of those survivors are in the circulated grades, often the WELL circulated grades. Many pieces have been badly worn, bent, holed and otherwise damaged.

All of this leads to the age-old numismatic question, is the 1792 half disme a pattern or regular issue? The classic answer has been “pattern.” This opinion dates back to the Sylvester Crosby who grouped it with the other 1792 patterns. Since then Adams and Woodin, J. Hewitt Judd and Randy Pollock have included it in their works on U.S. Patterns. It should be noted however that Adams and Woodin wrote in their work, first published in 1913, that, “This half dime could very well have been a coin of regular issue.” I respectfully disagree with those who classify the 1792 half disme as a pattern for the following reasons:

Mintage Pattern coins are experimental pieces that are made in very limited quantities in order to see how a given design will appear and strike up, sometimes in various metals. Mintages of more than 100 pieces are very unusual and are often driven by collector demand.

Depending upon whether or not you subscribe to the mintage of 200 to 300 pieces in the fall of 1792, the half disme had an undisputed mintage of at least 1,500 and perhaps as many as 1,800 pieces. Those numbers are much too high for a pattern coin.

Preservation As was mentioned previously, most of the surviving 1792 half dismes are well worn. From that it is obvious that these coins were made to be circulated and were used. The vast majority of patterns are Mint State or Proof and are usually found with little or no wear.

George Washington's 1792 Report to Congress To me, this is the most compelling argument for classifying the 1792 half disme as a made for circulation, regular issue coin. In his November 6, 1792, annual address to Congress (the forerunner of the modern State of the Union Address) George Washington said the following:

"In execution of the authority given by the legislature, measures have been taken for engaging some artists from abroad to aid in the establishment of our Mint. Others have been employed at home. Provisions have been made for the requisite buildings, and those are putting into proper condition for the purposes of the establishment. There has been a small beginning in the coinage of half dismes, the want of small coins in circulation calling the first attention to them."

The last sentence cinches the argument for me. If the President of the United States, our nation's chief operating officer, viewed these coins as "a small beginning in coinage," in the year in which they were made, how can their status be in doubt? The 1792 half disme was the first U.S. coin. It is hard to argue against that assertion.

Comments

happy holidays

The provenance of my coin includes the Dr. J. Hewitt Judd Collection and the Jimmy Hayes Collection.

The 1792 Half Disme is beyond my reach and I will likely never own one, but I appreciate the history behind it. Thanks for taking the time to share the history behind this piece and to dispel some of the myths regarding this piece of American history.

Donato